Gen X Family History Project in 9 Brutal Steps, Part 1

Converting the overwhelming boxes and piles of memories into a portable personal museum that will be a joy to own and easy to pass on for generations, PLUS Music & soccer that both brought me to tears

Gen X Family History Project, Part 1

(NOTE: This content will eventually be expanded into an e-book available for purchase. Enjoy this condensed and simplified version here for free. I am just so excited about the finished product that I can’t wait to share it with you.)

I don’t think you understand how overrun we were with stuff.

But we have conquered it. We have curated it down to something well-organized, easily accessible, compact and portable—something that can be painlessly handed down through generations, if anybody cares to do so after we are gone. And I’m going to show you, step-by-step, how you can do it, too. Hopefully, your situation is not as extreme as ours was.

When we relocated to Montana in 2004, we moved our family of four from a 2,000 square foot three-bedroom house with an enormous shop and a storage unit onsite, to a 1,000 square foot two-bedroom house with a two-car garage—and a built-in grandpa. The grandpa was part of the deal; his decision to keep all his earthly belongings in the house he had sold to us was not. Fortunately, he had cleared out the piano and the taxidermied bull moose, so the small living room wasn’t quite as full as it could have been, but the cupboards and the closets and the garage and the barn were already full when our two (TWO!) moving trucks arrived.

Over the years, instead of clearing things out, we continued to accumulate more. At one point, some unexpected tenants joined the military and had to leave many of their belongings behind. My husband’s parents moved in with us temporarily in 2007, planning to build their own home next door, but Mom passed away unexpectedly only a few months later. Dad stayed with us instead of building—and all their lifetime of belongings, as well as all the belongings of her mother they’d recently inherited stayed, too.

We were full to the rafters and then some, friends.

Then came the charity yard sales we hosted at our house, where generous donors donated all their excess to help send kids to summer camps. What happened to the leftovers? They went into our garage to wait for another sale, another year. Ugh.

In the fall of 2011, I put forth a herculean effort to trim down our belongings once and for all, but it was still not enough. Our neighbors were probably baffled about our annual summer garage sales—even after the charity event years were past. How can one family have so much stuff to get rid of? Each year, we thought we were making the hard cuts and trimming way down, but by the next summer, we would realize just how much further there was to go, and we would drag the sale signs back out to the road for yet another round.

Finally, just last year as we were getting ready to sell the house, move into a temporary one-bedroom apartment for just the two of us, and ultimately transition to a nomadic lifestyle, we had a living estate sale. We sold everything that wasn’t nailed down, and then we pried the remaining things up with a crowbar and sold them, too—the furniture and rugs, the lamps and Pyrex dishes, the extra towels and bed sheets and most of the books, the dusty antiques and the dumb collections, even the soap dispenser from the bathroom counter. Finally, we sold that crowbar, too.

We sold the special things, too—the art I had made myself that no one else in the family wanted, the décor that had originated as souvenirs from our international travels, the rusted ranch triangle I always rang to call the kids and dogs home for dinner.

At the end of the weekend sale, our home—which had grown over the years from the original 1,000 square feet to a sprawling six-bedroom monstrosity—was empty. We sat on the floor and gawked at the emptiness, our voices echoing off the bare walls. We were leaner than we’d ever been before, and it felt surprisingly fine. Once things went out the door, they were gone. We said goodbye and we watched them go, but we were happy they’d found new homes. We didn’t miss them. We were free.

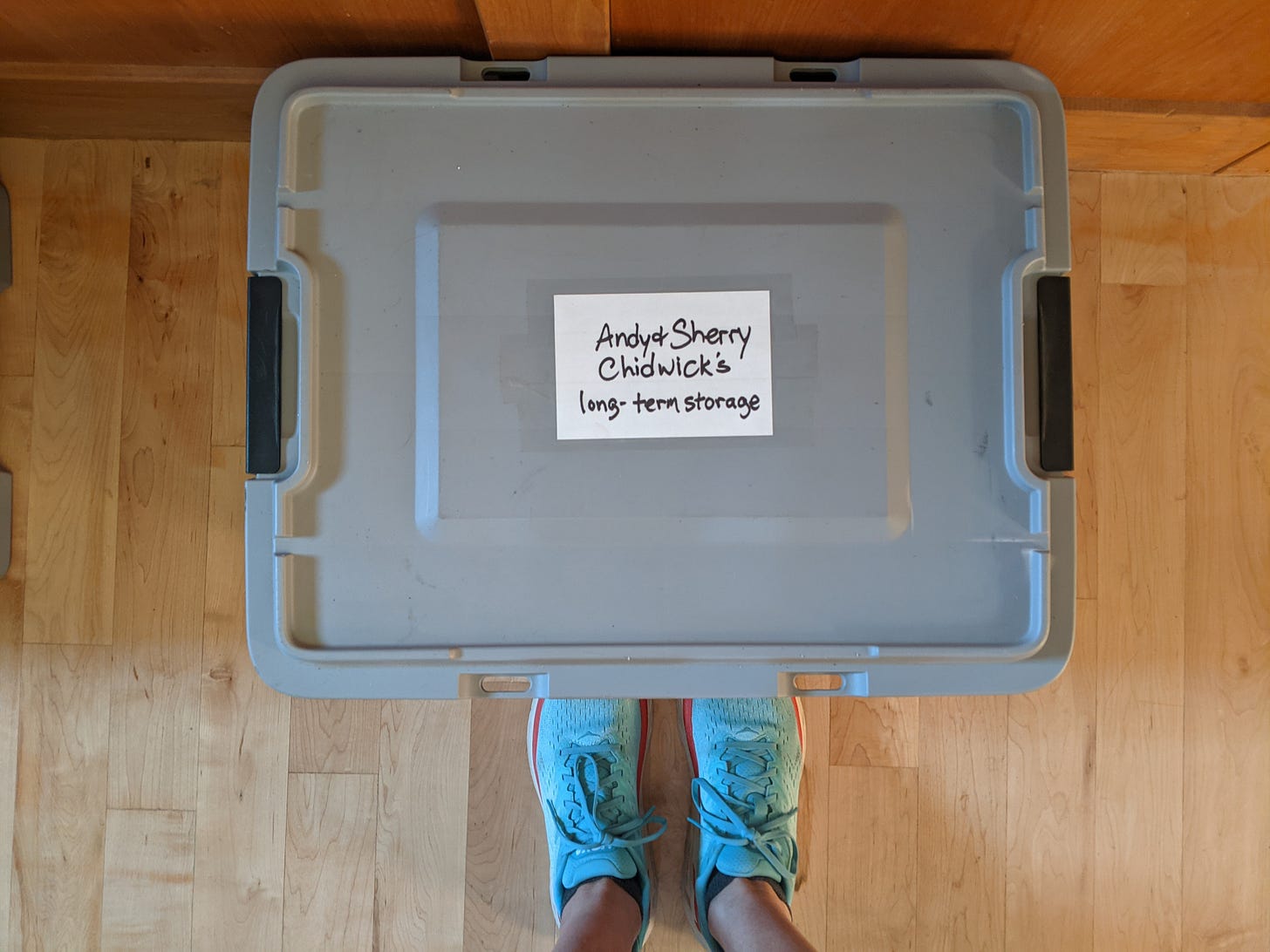

However, there was still the stuff in that one back room out in the barn. You know, the place that holds the stuff-that-shall-not-be-touched. The big cedar chest and all its contents from mine and my husbands’ childhoods. The dozen or so tubs that contained the record of our lives together—the tax returns interspersed with the owner’s manual for the long-deceased microwave and the warranty card for the camcorder, the kids’ drawings and notes and craft projects, the certificates and newspaper clippings and boxes of obsolete business cards, the trophies and the 4-H ribbons, the special event t-shirts and the borrowed books still waiting to be returned to their rightful owners. Then there were the photo albums, as well as the boxes upon boxes upon boxes of loose photos that never made it into albums. Remember the 1980s and early 1990s when we always opted for double or even triple prints of our photos, then sent copies to Grandma, who added them to her own boxes—which she brought along when she moved in with us? Yeah. Good times.

Here’s the problem, though—the generations younger than us, including our children, have grown up on digital storage as a mindset—a native language. With rare exceptions, they don’t want our stuff. They don’t look forward to a lifetime of being saddled with dusty boxes they have to move from place to place, but rarely ever open to use or enjoy. They grew up watching us complain about having too much stuff—particularly stuff that we unwittingly inherited from the generations before us—and they don’t want to repeat the cycle. Most of it is not going to be saved and treasured after we are gone. Most of our stuff is going to be considered junk within a generation—two, at best—and discarded.

If you have been tasked with dealing with your own parents’ or grandparents’ stuff after they passed, then you still remember the guilt and frustration that comes with being forced to decide what to do with piles of things that were obviously important to them, but have little to no meaning for you personally. Let’s not do the same thing to our own kids and grandkids. Let’s stop the cycle. My plan, as I am going to outline below in its nine brutal steps, takes Swedish Death Cleaning to a new level.

I avoided this job successfully for years. It was daunting, to say the least. But because we are soon going to be location-independent, I finally had to tackle it. Some would suggest that digitizing everything is really the way to go, but I disagree. I have looked through my Google Photos. It is a disorganized, bloated stash of images with no curation or commentary—just as overwhelming as the boxes and piles of prints. I wanted to hand down something physical, but manageable. Now my big project is finished—or 98% finished, at least. Full disclosure: I am still in the midst of finishing Step 9. I am so happy with the result—so happy that I want to share my system with you. Perhaps you will be inspired to do something similar. Perhaps we will start a new trend. Seriously, I wish I had done this years ago, even if we weren’t planning to become nomads.

Caveat: I don’t recommend starting this process without first reading through the whole thing and discussing it with your spouse or any kids still at home. It is a brutal process, and if you don’t have the support of the others in the house with you, there will be trouble. If you do have their support from the outset, they will rise up and call you blessed when you present them with the finished product.

Here’s what I did (and you could totally do, too):

STEP 1

Open every single bin and drawer and closet and throw away, sell, or donate all the heavy, big, or bulky things you can possibly bear to live without. When in doubt, snap a photo of it and text it to the person who might care about it the most. Tell them you need a response at their very earliest convenience, and you are fine with them saying no thank you. If they don’t want it, offer it to the next person who might want it, if there is one. Never make it available to two people at the same time! If someone would like to give a particular item a good home, set it aside—away from your active project area—to mail or deliver it to them. If no one wants it, just shrug your shoulders, repeat this sentence—“OH WELL; I TRIED,” and then immediately make it go away. Face it: if your kids will admit to you now, while you are still living, that they don’t want something, then you can be assured they will toss it once you are gone anyway. Do them, and yourself, the favor of clearing it out now.

For us, that meant the high school and college yearbooks had to go. The trophies had to go. The old leather motorcycle jacket and the hats from assorted baseball teams and the mother-of-the-bride dress had to go. All the special blankies and stuffed animals the kids didn’t want had to go (except for that one brown elephant with the red and blue plaid ears that I played with as a child, but which originally belonged to my father when he was a child—that one got to stay—more on that in Step 8). Some things were sold or donated; some were simply thrown in the trash.

A word of caution—this first step is the most painful one. If there are some important non-paper items that you consider part of your history, keep them. Set them aside for now and we will address them again in Step 8. If it belongs or belonged to your child, send them a quick text and see if they want it. If they do, set it aside in a box marked with their name. But once an item has made the cut list, get it out of view quickly. Put it in a trash can/bag and place something else on top of it so you can’t see it anymore. Be quick about this and, as is the key word in this process, be brutal. It gets easier as you go; trust me. After a couple of days of an item being out of sight, you may be surprised at how much you don’t care about it anymore. Start with the biggest things first, so you clear the most space at the outset. The extra space left behind is rewarding and will help you build momentum. Plus, making more space, both physical and mental, will be necessary for some of the stages to come.

STEP 2

Go through all your bins and shoeboxes and file folders of paperwork. All of them—like you are a machine. If there are things that cannot be discarded and must be filed away, like recent tax returns or financial paperwork, group them all together in a box clearly labeled KEEP and set them aside, away from your project area. You can file these essential things later.

If there are leftover business cards or brochures from your jobs in the past, set aside one of each for Step 8. Likewise, if there are some nice letters written to you or about you and they mark something significant in your life—or love letters sent between your grandparents, by all means, set them aside. Feel free to keep a copy of that newspaper article, the syllabus for that class you taught, the official certification of that big milestone you accomplished, the pages of genealogical research your mother did, your wedding invitation, etc. Anything that symbolizes or documents an important part of your life—if it is still special to you—keep it, at least for now. Place these papers in a box clearly labeled KEEP and set it aside to make more space.

Discard all the paperwork you don’t need or care about—and again, be quick and brutal. Don’t bother to stack neatly. Toss. Move on. For documents that contain personal information but can be discarded—the mortgage you paid off on the house you sold in 2018, or the car registration and insurance from your 1989 Camry, make a separate pile. Later, you can run these things through the shredder or feed them to the fire pit on the back patio while sipping a beverage with a friend. Right now is the time to continue to clear out space. Can you feel your lungs filling with air as the storage area empties out? Don’t breathe too deeply, though; it might be dusty in there.

STEP 3

Take all the photos OUT of your photo albums and picture frames (unless the frame is already on the wall, and you like it there). You won’t need those stored frames or albums anymore—even if you did (like me) spend days back in 1993 decoupaging those albums with pieces of maps and covers from old National Geographic magazines. Ouch. Make them go away now—quickly before you lose your nerve. Keep the photos but discard the albums and frames. They take up too much space. Don’t worry—we will deal with all those photos in Step 5.

STEP 4

Now that you are finally ready to begin your family history project, gather the supplies you will need. I recommend the following:

10-20 two-gallon sized Ziplock bags (one gallon size is TOO SMALL)

20-40 quart-sized Ziplock bags (XL sandwich bags also work, but not standard sandwich bags)

2 trash bags

20-50 blank 4x6 notecards

2-3 reliable ink pens

2-3 new-ish medium-point Sharpie markers (not fine tip, but not old and blunted down ones, either)

scissors

2-4 clean and sturdy storage bins with securely-fitting lids and heavy-duty handles

CLEAR packing tape

(TO BE CONTINUED. Click here for Part 2, Steps 5-9.)

Montana International Choral Festival and the FIFA Women’s World Cup:

Why they both send tears streaming down my cheeks

When our kids were young, my friend Nancy and I used to take them to the Montana International Choral Festival, an event that occurs every three years in nearby Missoula. The first day of the 3–4-day festival is always free, which always worked well into my meager budget during those years.

The design of the festival is remarkably simple. Highly talented singing groups, generally a cappella, are invited from all over the world to come and sing in various locations around town over the course of four days, culminating in a big joint concert of all of them performing together—one voice, from many nations.

Oops, there I go, tearing up again. Any time nations of the world come together in peace to share the celebration of their joy together, I get all verklempt. Seriously, the Parade of Nations at the opening ceremonies of the Summer and Winter Olympics? I am a mess every single time.

I hadn’t been to the Montana International Choral Festival since my kids were young, but this year the opening day fell on my husband Andy’s birthday. He had never been, so we decided to take a picnic and make a day of it. The concert in the bandstand of Caras Park, on a grassy lawn next to the river under a flawless blue sky, was the stage for the official introduction of each of the choral groups. Each of the ten nations represented presented three pieces, just enough to whet our appetites for more, of course.

After the event at the park, we walked downtown, in the midst of the large choral group from Taiwan who were headed the same direction, to hear them and two other groups perform again in the historic Florence Building. Its two-story art deco lobby trimmed with marble and hardwoods provided incredible acoustics without the need for any microphones.

Under the guidance of some incredibly talented directors, the skillful sounds of each group reverberated through the lobby from their perch on the balcony of the second floor. The harmonies—clearly distinctive sounds, but blended seamlessly into full and rich chords, played my heart strings like the bow on a cello. I closed my eyes and imagined a world as unified and peaceful as the sounds I was hearing. It was glorious.

It made me itch to travel. After each group’s performance, I turned to Andy. “Let’s go to Estonia!” or “Let’s go to Costa Rica!” or “Let’s go to Poland!” I would say. He would grin and agree.

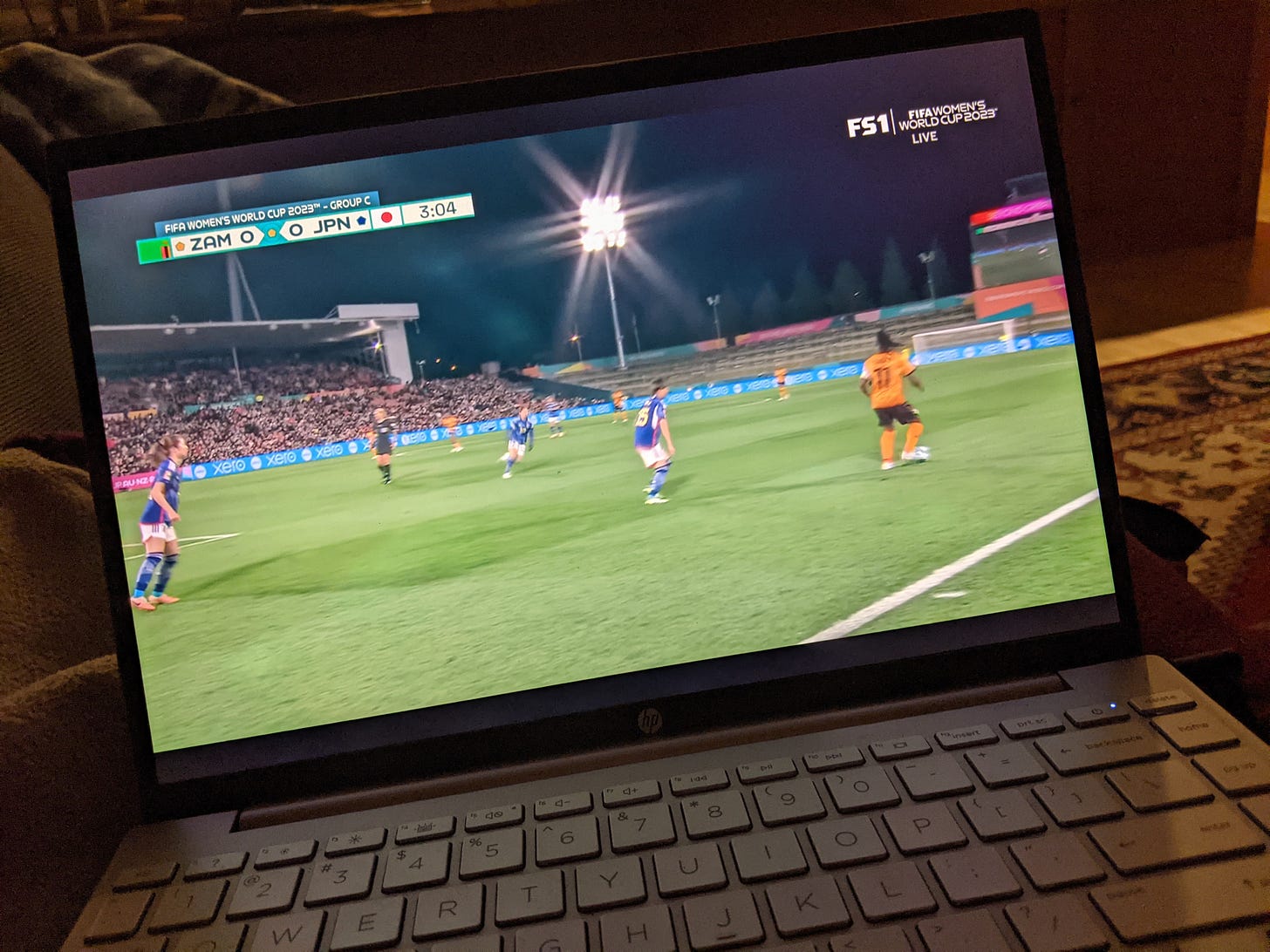

Only a few days later, the FIFA Women's World Cup, the once in every four years sporting event, began. Zambia, the land-locked African nation where some of my extended family lives, is in the tournament for the very first time—including both men’s or women’s squads.

This year’s tournament is being held in Australia and New Zealand, which means many of the game times are awkward for North Americans to watch live, but I was determined. For Zambia’s first appearance on this world stage, I got up at 1:00 AM and donned the orange and green team jersey I found on eBay; then I tip-toed to the living room, slipped on my headphones, and opened up my laptop. The opening whistle blew for their match against Japan, a precision powerhouse of a team. As is the case with most debutants, Zambia’s Copper Queens lost badly.

But I smiled the whole time. I was so proud of Zambia for coming so far. I was so happy to watch a game of sport played between two groups of people who physically looked so different from one another; and verbally, would not be able to communicate well. Yet even in the midst of their fierce competition, they stopped to help one another up when someone needed a hand or committed an accidental foul. The tears welled in my eyes the first time I saw it, even in my middle of the night fog. This is what the world should be.

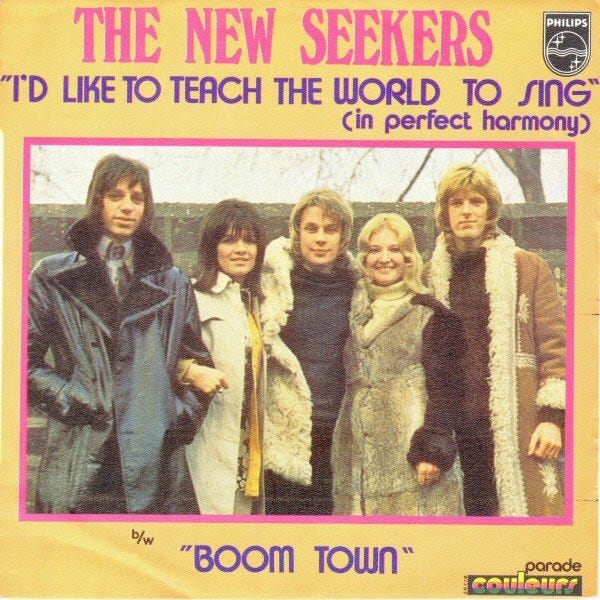

“I’d like to teach the world to sing . . .”

I am looking forward to your ebook. I am currently the keeper of family pictures for my father’s family and am still dealing with the accumulation of my in-laws.

Way better seeing a happy face taking your art. I had 2 sales before moving. Though some things were hard to part with, some things I was so happy to be rid of. :) I had my dad's old train set, that he played with as a kid and us kids played with, always had it running around the Christmas tree, and reluctantly boxed it up a couple years ago and took to a niece and her family in Phx - they couldn't care less. Sigh