Finding the limits of Walter and me

The day in Baja when the stress became too much, and I had to seriously reconsider my life choices

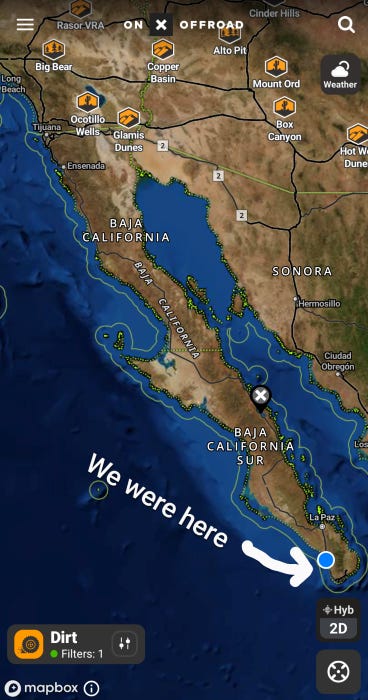

The worst part is, it was my idea. I was the one who found the trail on OnX, an offroad navigation app we use when we want to explore places a little more scenic, a little less main highway-ish.

I was the one who said, “Hey, check it out. This road isn’t far from where we are now, and it could get us way up onto a rocky bluff. The views would be spectacular. If the whale watching is fun from the beach, just think of how amazing it would be from up there.”

I was the one who had zoomed in and noted what looked like a graded level area at the top of the hill where we might be able to camp—outside the reach of the overnight parking bans that seemed to reign supreme in charming Todos Santos.

It was labeled green for easy, a level three off-road trail on a scale of one to ten, and the road was only two and a half miles long. How bad could it possibly be?

By the time we found out the answer to that question, it was too late. The dry desert road was narrow and steep—no place to turn around and darn near impossible to reverse our way out.

Walter, our big yellow adventure truck, is a beefy four-wheel drive with extra high clearance underneath, but he is also over eleven feet tall and shaped like a toaster; a rocking and swaying toaster built on a chassis that might otherwise support a mid-size U-Haul truck.

Our current travel companion, Cristin, zipped on ahead in her svelte Toyota Tacoma1, a rig she specially designed for off-road driving and off-grid camping. Walter, on the other hand, is not so nimble.

After some initial tree trimming to even get past the first hundred meters, the road hugged the rugged mountainside most of the way up. Vertical walls hemmed us in on one side while the other side—the side with the certain death drop offs—was punctuated with frequent rockslides and washouts. At some places, the road narrowed to slightly less than wide enough for one vehicle’s tires to fit and Walter had to climb partway up the inside wall so we could continue on. At other places, the washouts had dug such deep ruts that the road itself tipped precariously to one side. Fallen rocks jutting up jagged and sharp—many of them large enough to stop a lower-clearance vehicle in its tracks—littered the sandy surface. The steeper portions challenged our gearing on the uphills and our brakes on the downhills. And, of course, each steep grade contained a sharp switchback turn at the apex, just to sprinkle a little extra chili powder on the experience.

My husband Andy thought I was joking and just being dramatic at first when I clutched the arm rest, gulped oxygen like a fish on the beach, and declared, “At this point I have to seriously reconsider my life choices.” He didn’t realize I was accelerating from Fun and Adventurous Sherry to Full-Blown Panic Sherry with each new obstacle in our path.

I actually thought we were going to tip over, roll down the cliff, and die. Or, worse yet: I feared we might tip over, roll down the cliff, and live—with horrific injuries.

I am not a person with a background in four-wheeling for kicks and giggles. And this particular road was treacherous, no laughing matter even for Andy, who generally enjoys such challenges. Although he was working hard to remain calm, carefully picking out each line to traverse, I could feel his own stress mating and multiplying with mine like an unchecked colony of wild rabbits. We didn’t know what was around the next bend in the road. We didn’t know the capabilities and limitations of a rig like ours. We didn’t know for sure that it was built properly (by us amateurs) to handle something like this.

After a few minutes of climbing and twisting and struggling, I was white-knuckling every possible handhold within reach, nearly hyperventilating, and making squeaky-voiced remarks about how I seriously might need to get out and walk. Andy realized how stressed out I was and did his very best to calm my fears and help me see the adventure in our predicament. But exhilarating, challenging, and fun didn’t cross my mind as situation-specific vocabulary words at the moment.

My pounding heart felt like it was at its absolute maximum—like the heartbeats, plural, had joined hands and solidified into one enormous BEAT that was stuck at the top of the metronome. I needed to pull it together. I focused on remembering to breathe, coaxing every bit of willpower I could muster to get on top of my panic and press it back down. I needed to be functional so Andy could focus on the road.

By the time we reached the top, however (and we did reach the top and find the gorgeous campsite I had hoped for), I was struggling to hold back tears. I was safe, out of the truck, and on level-ish ground. But my stress while climbing that road, turn after harrowing turn, with the truck lurching and jolting and rocking, had reached a level I don’t think I’ve experienced since that one time in the terrifying Southern California summer of 1985, when I was home alone and convinced the Night Stalker was trying to get into my house.2

The bluff-top was blustery but beautiful, as expected. Exhausted and yet still keyed up with adrenaline, I managed to block up our wheels to level our truck for camping, but I could feel my tension tanks were overfilled. I needed to find a release valve somehow, somewhere—and soon.

A simple hiking trail led away from our truck and through the severe landscape of cactus and spiny shrubbery out to the end of a rocky point. Andy and I walked out there, hand in hand, and gazed down at the tiny white caps dotting the deep blue Pacific Ocean, rimmed with emerald and turquoise, some 500 feet below. Slowly, my heart rate returned to a manageable rhythm. The emotional tension, however, remained high. The pent-up stress still needed somewhere to go.

Cristin wisely opted to walk on to a different viewpoint, leaving Andy and I alone to talk.

Yes, my midlife mantra is “I am comfortable being uncomfortable.” Yes, I want to learn and grow at every possible opportunity and not succumb to the stagnation that often comes with aging in place. Yes, I have always liked the challenge of doing hard things and I am not about to give up that part of me. Yes, this is what our Nomadic MidLife3 adventure is all about.

But this time it was too much.

This time it was me, my husband, and our home, all angled precariously on the side of a cliff, trying to climb impossibly steep grades over big rocks and deep ruts. This was not my idea of a good time. This is not the life I thought I’d signed up for when we decided to build an adventure truck and travel the world. This is not what I want for our future. It was terrifying for me. I was embarrassed; humiliated at my own weakness, my own limitations, but it was honestly too much for me and I needed to admit it aloud. I can usually put on a brave face and bear most anything, but this was too much.

To my great relief, Andy agreed.

He agreed.

I breathed into his chest and let him hold me close while I gazed out at the vast blue horizon. My stress leaked out the corners of my eyes, mapping a labyrinth of serpentine roads down my dusty face.

Too much. Too dangerous. Too stressful. Too much to ask of our bulky and unwieldy home on wheels. Too much to ask of me.

He agreed.

Through that experience, we found that Walter is technically capable of traversing a path like that. But we also found what we believe is our limit. And neither of us wants to repeat or exceed it.

Later, I explained to Cristin how little background I’ve had in activities like this, and how hard the experience had been on me. I admitted I was still on the verge of tears even then, half an hour later. She gave me a huge hug. Her compassion undid me, and my tears fell again. She didn’t look away. Instead, she said she was proud of me. We had a little moment there, 500 feet above the sea, while the sun blazed and the wind buffeted, while the turkey vultures glided in wobbly circles above, while the whales spouted and the sea lions barked far below.

Looking back at the route, Cristin (who happens to map trails for OnX as a side income), disagreed with the write-up for that road on the app. “There’s no way that trail should be classified a three. That should have been a five, at least.”

I was so glad to hear that. I’m not a complete and total wimp. It was hard. It felt terribly dangerous. Her Toyota is made for such things. Our Walter Mitsubishi big rig is not.

We all agreed. A truck like Walter is very capable, but climbing the Puerto Viejo trail maxed it out. We will continue to challenge ourselves to get to amazing remote locations in the future because Walter was designed to do just that, and we enjoy it. But we will try to keep our future experiences to less than the worst of that trail’s level.

Of course, we still have to get back down. While we’re up here on this bluff, I’m trying to enjoy myself—hiking and exploring and observing the wide variety of cactus species just coming into bloom, morning campfires when the air is still, and watching whales and the occasional pod of dolphins gracefully slicing through the waves. But just below the surface I am nervous, dreading the return trip.

Success

We made it down without incident. Walter didn’t tip over or fall off a cliff. He didn’t get high-centered in a deep rut or blow out a tire.

It was not exactly the same route in reverse, though.

First, before we even attempted the return trip, the three of us walked ahead to the steepest, most washed-out portion of the road and stacked big rocks into the deepest ruts to make it less treacherous.

Second, Andy aired the tires down considerably this time. They looked flat enough to be concerning in most driving situations, but it was the right thing to do in this situation, adding surface area and traction and the ability to slowly and softly eat up uneven terrain without bouncing. It made a huge difference in the truck’s performance on the way down.

Third, we knew the condition of the road from start to finish before we began our descent, allowing us to more confidently approach what was at the end of each steep hill and around each bend. This time we knew we had the ability to traverse it, even if it took half an hour to cover the two and a half miles—which it did.

Once we were all back on a level, full-width road, we aired the tires back up for highway driving and celebrated with the last of the ice cream bars Cristin had been keeping in our freezer. Between bites of chocoalte-toffee-covered-vanilla, we breathed sighs of relief.

We learned so much from this experience. We will be more confident and wise next time we are on dangerous roads.

But it’s not really even about becoming better 4x4 drivers. It’s more about becoming better students of the world around us, better decision-makers. It’s about processing fear and sharing vulnerability. It’s about becoming more supportive partners, more willing to honestly admit our thoughts and feelings. It’s about leaning into friendship for support, rather than insisting on false confidence and independence all the time. It’s about humbly admitting weakness, not letting it smother us in shame, and letting the tears fall where they may.

When we left our life as teachers to live as nomads, traveling the world without a home base, we knew we would need to move from the front of the classroom to the back, from the confident teacher’s podium to the struggling student’s desk. We had a lot to learn. I didn’t stop to consider, though, that the learning curve would be anywhere near this steep—that I would feel this on-edge, this off-camber, this out of my comfort zone.

Oh, and did I mention that we also got stuck in deep sand on a beach for the first time this past week, too? Every time we’ve driven on a beach, I’ve been concerned about getting stuck in the sand. It finally happened. But I didn’t panic. We were on level ground, near a town, with a travel buddy and plenty of resources around in case things went wonky. The sand was soft and clean where we knelt, almost reminiscent of childhood playtime. As we worked, the blazing sun fizzled gracefully into the sea, lighting the sky dramatically all around us. Getting stuck on the beach was not what we’d planned for the afternoon, but although I’d worried about it in the past, it wasn’t terribly stressful when it actually happened. We simply dug ourselves a path, laid down our traction boards, and cheered as Walter roared to life and drove away, toward firmer ground.

We live and we learn, right?

The world is our classroom and experience is our professor. Unlike the school where we taught before, in the education system we’d always known, now our lessons begin at odd hours, often when we least expect it. No bells ring through the halls to signal the time to slam our books shut, zip our backpacks, and file out. Homework comes sometimes in enormous loads, and sometimes not at all. And the learning doesn’t always come naturally. Often it takes hard work—physically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually. Whoosh. So much learning.

What is the life you want, friend? What are the risks? What are your worries? How do you process your fears? What are you learning along the journey?

Until next week,

Sherry

P.S. If you want to know more about the Diesel & Dignity Fund and the goals of this travel blog, please check out last week’s post about how I’ve been spending your subscription dollars. And to you new subscribers, welcome! I’m so glad you’re along for the ride.

Our new friend Cristin and her super cool truck (which she designed and built) are on Instagram under the name @badassbrunette.

In my defense, someone WAS trying to get into my house that night in 1985 (long story), and we DID live in a yellow/tan/beige one-story house near a freeway onramp, which seemed to be the Night Stalker’s most common target, and it WAS a really big life-altering deal for me. It was the first time I’d ever faced what I truly believed to be certain death and the panic in my chest pounded fiercely. Eventually, when I realized there was no way out, though, I was ok with it. I was strangely at peace. I wasn’t looking forward to the method of death, but I was not worried about the end result. For more on the Night Stalker, serial killer Richard Ramirez’s story, click here. For more on what it looks like to face one’s own certain death without fear, contact me personally. BTW, it wasn’t the Night Stalker or any other heinous criminal trying to get into my house that night. It really is a long story, but I was ok.

For more about our Nomadic MidLife adventure, you can check out our website, here.

I could feel the fear in your voice and recalled it in my body when facing similar situations. This is it. This is the end! It’s quite an experience. I’m grateful you made it through and… there is a lot to be said for walking ahead as well as having a spotter on the ground instead of the passenger seat.