The classic black and white border collie had likely seen better days. Her fur was dull, not shiny, and her legs were wet up to her belly—probably from the pond. One ear flopped to the side while the other one swiveled like a satellite dish receiving incoming transmissions. The dog crouched on the pavement, just out of reach, her eyes darting back and forth between the locals and me.

I motioned toward Walter, our big yellow adventure truck, which was still parked behind me where we’d camped for the night. “My kitchen’s right here. Do you suppose she’d like leftover grits?”

“I reckon she’d eat whatever you got. Poor thing got abandoned here at the park last week. We been tryin’ to catch her, but she’s too sneaky. Scared to death. I just don’t know how people could be so cruel.”

I climbed back up into the Snuggery and slid open our chest fridge to find the leftovers. Then I hopped back down, set the plastic container on the ground, and gave it a shove. As the little tub of grits skittered across the pavement into the open area between us, the dog perked up, her nose twitching with interest.

“I put a little scoop of tuna salad in there, too, so it would smell good to her.”

The pup gobbled up everything in the container, checking the corners for any stray morsels, then looked intently at me and licked her lips. Her communication was clear, and we all chuckled.

“I’m guessin’ she’d like a little more of that, if you got any.”

“Of course. Poor thing.” I climbed back up inside, unlatched the fridge again, and scooped some more tuna salad out with my big red serving spoon. I climbed down carefully, balancing the red spoon, and approached the dog slowly.

In a move only a hungry but frightened dog could invent, her legs moved in reverse while her nose managed to move forward, fully aware of her vulnerable situation. I reached the empty container, crouched down, and shook the contents of the spoon into it. She bravely inched toward the tuna and me at first, but then I made the mistake of banging the spoon on the rim to shake off the bits that were stuck. The dog flinched hard. Her ears dropped and she jerked her body backwards, out of harm’s way.

“Aw. Don’t you worry, sweetheart. She ain’t gon’ hurt you none.” Then, turning to me, “Poor thing musta been hit in the past. What a shame.”

“How could a person treat a dog so bad?”

As former teachers, our goal is to be students again—students of the broader world, far beyond the places we’ve lived in the past. After leaving North Texas, we’d set out for our next destination, Atlanta, Georgia, by way of Arkansas, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama. We hadn’t researched ahead of time. With a quick glance at Google Maps, we’d planned the route for its relative expediency, not its historical significance. But soon after we set out, we found ourselves smack-dab in the middle of a mid-century modern debris field.

Wednesday morning started out lovely. We’d awoken early in a quiet highway rest area in Arkansas—just far enough off the road and into the trees to block much of the noise, and pleasantly underutilized because the signs on the highway had cautioned the restrooms were out of order. After a quick breakfast, we rolled out of our quiet campsite and set our face toward the Anytime Fitness in West Memphis, just before the Tennessee state line. Whenever the opportunity arises, we love to start the day with a sweaty workout followed by a luxurious hot shower. Leaving the gym, we ran across a mural painter and a man who had stopped to admire her work. Both paused to gawk at Walter as we sat at a red light, so we visited through the open window for a moment, then pulled over and parked so we could get out and chat. Twenty minutes out of our day was a small price to pay for the stellar conversations we had in that short time. Then we hit the road again, all smiles, fresh and clean, and ready for a pleasant day of driving.

Only a few miles down the road, though, we passed a sign for the National Civil Rights Museum at the next exit. Our lighthearted conversation stopped. Silence hovered for a brief moment, then I spoke.

“Did you see the sign for the museum?”

“Yeah. Have we been to that one yet?”

“No. We went to museums in Little Rock and Atlanta way back when, but I think the only thing we did in Memphis then was hang out on Beale Street.”

“Right.”

More silence.

We both knew our day, and perhaps our week, would be changed if we stopped.

Intentionally focusing on painful things has a way of doing that. When we backpacked through Cambodia and Vietnam last winter, going to a history museum often left us stunned, quiet for days afterward, contemplative and full of questions—and sad.

But we were inadvertently passing through the heart of the nation’s struggle for racial desegregation. We could ignore it and enjoy the blue sky, sunshine, and upbeat music playing through Walter’s speakers, or we could stay true to our character and our goals of learning about the places and people we meet.

“This seems like the type of place we should go.”

“I agree. We do have a few hours we could spare today. Do you want to stop?”

“I think we should.”

We turned at the off-ramp, both literally and metaphorically, and committed to traveling more slowly over the next few days, tracing the path of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. The detours would decelerate our travel pace and cheerful mood—not part of our plan, but we try to hold our plans loosely, with an open hand. For us, it was important to go to the sites. We wanted to learn. We needed to pay our respects. It might not make a difference to anyone else, but it mattered to us. For us, shying away from the difficult topics is often more painful, long-term, than facing them.

Having still done no research, we parked the truck on a side street and followed the other tourists and school groups toward the museum. When we came around to the front, our feet stopped, frozen in place. We stared up into the face of the Lorraine Motel, a scene immediately recognizable from historical photos we’d seen—Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated there on the balcony of Room 306. The motel, now restored to its April 4, 1968, 6:01 PM condition—complete with the cars that were parked there at that moment—felt like a movie set.

But this was not Hollywood.

Over the next several hours, we dutifully read, studied, listened, looked. The museum was skillfully crafted. Life-size displays allowed us to stand in the crowd at a 19th century slave auction and a 20th century lunch counter sit-in. We stepped aboard the bus where Rosa Parks sat and, with her, faced the scorn of the bus driver, who was turned around in his seat. We examined the burned wreckage of another bus, a Greyhound carrying Freedom Riders who dared to sit interracially wherever they wanted. We walked up the Edmund Pettus Bridge among the marchers on what would be remembered as Bloody Sunday.

Over and over, I ignored my self-protective instinct to look away, walk away, stop engaging with such painful topics. But there is so much to learn for people like Andy and me. In years gone by, we’ve studied this era of American history of our own initiative, beyond the extremely limited information we received in school, but there is still so much we don’t know, so much we haven’t fully internalized.

We had to stay. We owed it to the past, to the present, to the future.

Not generally one to purchase kitschy souvenir items (or any items at all, now that we’re dedicated minimalists), I wanted something tangible this time. I knew exactly what it was, and hoped it existed in the gift shop. It did. As the intercom announced the museum would close in a few minutes, I purchased a replica of the Lorraine Motel key chain for Room 306. Then we drove away in silence, giving time and space to grow the seeds of knowledge we’d just watered. Seeds, of course, germinate in dark places.

The following morning, after camping in the parking lot of Veterans Memorial Park in Tupelo, Mississippi, we met a few locals concerned about the abandoned dog mentioned above. How could humans be so cruel, they wondered. As I approached the traumatized dog with the additional red spoonful of tuna salad, my movements unnaturally slow and gentle, my speech abnormally soft and soothing, I flashed back to the disturbing scenes I’d witnessed at the museum the day before.

How, indeed, could humans be so cruel, so inhumane?

I rinsed the spoon and the grits container, closed the habitation box’s windows, latched the refrigerator and the composting toilet, checked to make sure all the cupboards and drawers were fastened shut, and climbed out of the Snuggery and into Walter’s cab.

We drove on. Along the highway, glossy green grass luxuriated in long, unkempt tufts, still exuberant in its wildness since the mowers hadn’t yet arrived for the season’s first trim. Delicate new leaves in shades of lime and chartreuse dotted the dark trees. Dogwoods and redbuds and wisteria added frequent cheerful bursts of color. But it was only a small solace. The road signs reminded us every few miles we were headed straight for what was once known as the most segregated city in America: Birmingham, Alabama.

Although we weren’t even there yet, our hearts felt the dread, the heaviness of memory.

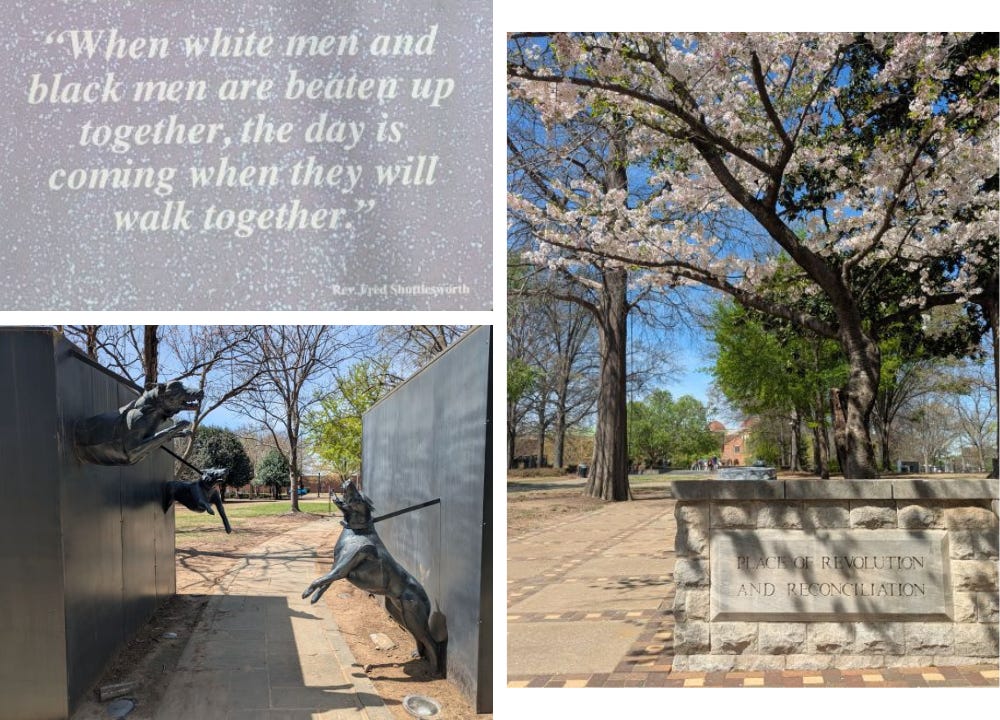

Walter rolled to a stop alongside Birmingham’s Kelly Ingram Park. In May of 1963, hundreds of teens and children gathered at the 16th Street Baptist Church, a historically African-American church across from the park, and marched peacefully down the street. Some carried signs and some walked empty-handed, their arms down at their sides. They’d hoped to reach the mayor’s office to talk about issues of segregation, but they didn’t make it. Police chief Bull Connor had his officers arrest 600 of the kids and packed them into the city’s jail cells and makeshift overflow holding areas at the fairgrounds. Many were released hours later, as there were not enough resources to process that many people—particularly children—at once. The next day even more young people showed up to try again. This time, they were met with force—batons, attack dogs, water cannons, and high-pressure fire hoses. Photos of the brutality spread across the globe like a wildfire fueled by gale-force winds.

We walked through the park, now a contemplative space containing numerous memorial sculptures. Some of the sculptures only asked for people to stop and notice. Others were interactive. We walked down a narrow sidewalk between walls embellished with snarling and snapping dogs lunging at us from both sides. We stepped through a doorway in one sculpture to find water cannons aimed at our faces on the other side.

The sculptors were asking us to stay present; to not ignore the way humans have treated fellow humans.

In September 1963, a few months after the children were attacked, a group of Klansmen from the town planted 19 sticks of dynamite outside the basement wall of that same Baptist church, during the brief time between Sunday School and the morning service. Four young girls were killed in the explosion. Twenty-two other people were physically injured. The shockwaves reverberated far beyond the city of Birmingham.

I placed my hands on the stone walls of the repaired church building, still in use today. I walked up the front steps where history had walked. I looked down toward the park, listening, searching, picturing the chaos on the street—both from the church bombing and the Children’s March the previous May.

With heavy steps, we walked from Kelly Ingram Park to the nearby A.G. Gaston Motel, a frequent meeting and lodging spot1 for civil rights activists and other African-American travelers. Now part of the National Park Service, it’s been restored to its 1960s appearance, frozen in time. Next door now, in the space once occupied by the motel’s restaurant, is Alicia’s Coffee. We stopped in and found it to be a vibrant Black-owned-and-operated business dedicated to bringing the community together and continuing the conversation about healthy race relations. We found friendly people there willing to talk, answer our questions, and share their opinions. We left there encouraged at how far Birmingham—now a vibrant, welcoming, multicultural city—has come since the dark days leading up to the mid-1960s.

There is always still work to be done, but remarkable progress has been made.

Although we would have liked to stay in Birmingham longer, both to hear more stories and see the hope of reconciliation represented there—as well as to rest our weary hearts—we had to move along. We wanted to make one more significant stop before the day was through. Although we knew it would come at somewhat of an emotional cost, we wanted to pay our respects to Anniston.

Another campaign of the tumultuous 1960s Civil Rights Movement—when activists finally organized and took on segregation with coordinated efforts—was the Freedom Riders demonstrations. The very first of these efforts, in early May 1961, set the tone for the many more that would follow.

Interstate bus routes, which originated in non-segregated states, but later passed through strictly segregated ones, were targeted by teams of people trained extensively in the art of non-violent resistance. The teams themselves were fully integrated—of mixed race, gender, and age. Their mode of operation was to simply sit on the bus and ride, as if any person were allowed to sit in any seat.

The audacity.

As could be expected in that day, the buses were not well-received.

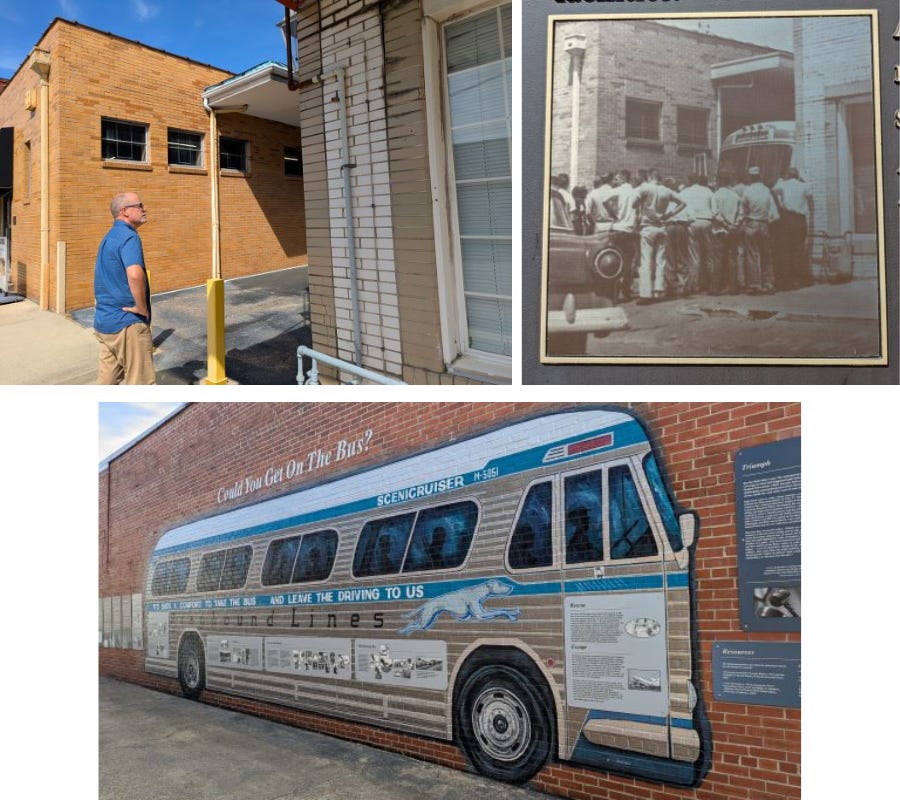

Roughly along our own travel route, we detoured to Anniston, Alabama, to see what we could find. The Greyhound station, the site of the very first Freedom Ride attack, has now been preserved as a National Historic Site. We stood in the loading and unloading alley next to the station where a Mother’s Day mob of angry men, some still in their church attire, surrounded the bus, rocked it back and forth, smashed the windows, and slashed the tires.

The driver pulled away from the station, but didn’t get far. Six miles down the highway, with the tires completely flat and the bus unable to continue, the mob—which had followed in private vehicles—attacked again, this time with firebombs. The passengers barely escaped with their lives. Two hours later, another bus carrying Freedom Riders2 was attacked at the Trailways Bus Depot, also in Anniston. All that remains there now is a mural and some informational signs, but we went there, too, so we could stand where they stood.

Eventually, we reached our destinations in Georgia, visiting friends in Atlanta and Hartwell—lots of hugs and laughter and catching up on each other’s lives. We temporarily set aside the heaviness that had ridden along with us as we passed through the full-color realities of the black and white images we’d seen.

But the past is always close to the surface everywhere you go.

We occasionally see various Confederate flags flown here in Georgia, as well as monuments erected to honor “heroes” of the Confederacy (those who found it more gallant to withdraw from the United States and fire their weapons against it, than to allow their slave labor-based economy and resulting lifestyle to be jeopardized). I won’t debate the controversies of the monuments here, as it’s a highly sensitive topic and deserves more focused attention, but I know those monuments still cause many of our dark-skinned neighbors to flinch. In many cases, it’s the very thing they were designed to do.

Andy and I, when retracing the steps of historical events, often look for where we would have been in the stories, had we been in that place at that time. Would we have applied to be trained as non-violent Freedom Riders? Could we have passed that training course? Would I have had the courage at 12 years old that young Janie Forsyth McKinney3 did when she brought water to the Riders whose bus had been burned in front of her father’s store? Would I have driven a carpool for the women participating in the bus boycotts? Would I have marched hand in hand with my darker skinned brothers and sisters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge or through a downtown street lined with dogs and firehoses?

What would I have done then?

What am I willing to do NOW when faced with injustice?

Tragically, generations of brown-skinned people and other minority groups in the United States have lived with trauma caused by their fair-skinned, majority-culture neighbors—people like me. Some of us—in days recent or long past—have voted for or even actively perpetuated the discriminatory treatment of others who are not like us. Others of us have taken a more passive role—not actually causing the problems, but not helping with the solutions, either. We haven’t stood up courageously for the most basic human rights and dignity or consistently shown Jesus-style compassion.

Some of the trauma has been passed down genetically through the generations. DNA research has shown this is a real thing. Some of it is still fresh and raw, experienced in person in this modern era.

How could we be so cruel? How could we treat our neighbors, our fellow humans made in the image of God, so poorly back then? And what about now?

I will remember the border collie, abandoned at the park in Tupelo. I’ll remember how she was so frightened and desperate, flinching when I tapped the big red serving spoon on the side of the leftovers container; how everyone present that morning understood she’d been hurt, and we all instinctively knew it would take extra love, extra gentleness, extra time to build trust with her. As much as she wanted human kindness in her life, she’d been burned before. It was hard for her to believe cruelty wouldn’t rear its ugly head yet again, so she was cautious. She was safe with us, but she didn’t know it. She didn’t feel it. So, she didn’t trust us, even when it was in her best interest. We would have to go above and beyond to prove it to her.

Is it rude to draw such parallels between humans and animals? Probably.

Humanity often treats animals more humanely than fellow humans.

Let’s go out of our way this week, friend, to show extra kindness to someone who is different from us in some way—whatever form of “different” it might be. True kindness is not the same as simply being nice. Kindness, above and beyond what is expected of us, changes both of us for the better. Kindness is good for the soul.

Until next week,

Sherry

P.S. I’m sorry I couldn’t write about our first ever trip to the Piggly Wiggly. It was so significant and unexpected, but I just couldn’t work it in this week. I guess I’ll have to save that story for the book someday. BTW, we will soon head north, roughly toward Canada and Alaska. But you know we easily get distracted. Geographic efficiency is not always our strong suit. Follow along with our nomadic adventures by subscribing below, if you haven’t already:

And if you found this article valuable, please share it with a friend.

A guide called the Green Book was published regularly to provide African-American travelers necessary information about where they could safely stay, eat, socialize, and shop in the face of Jim Crow laws.

Many Americans were frustrated with the Freedom Ride movement. Some felt it promoted widespread social disorder. It did—but not by the protesters themselves, the segregationists were the only ones acting out with violence. The brutal photos leaked to the press attracted so much attention during the jittery Cold War years that President Kennedy was afraid it made America look divided and weak in the eyes of Russia. Indeed, it did. But the riders kept coming, by the hundreds, stubbornly refusing to fight back as they endured beating after beating, firebombing after firebombing. If only to improve the U.S.’s public image, the violence had to be stopped. Not coincidentally, within six months after the Freedom Ride protests began, bus stations, train depots, and airports were completely integrated—racially segregated seating, drinking fountains, restrooms, lobbies, and lunch counters were outlawed in facilities that served interstate travelers.

Read or listen here to a 2017 interview with Janie Forsyth McKinney, recollecting that fateful day when the Greyhound bus was firebombed outside her father’s grocery store, and she, at only 12 years old, had the courage to bring water to the injured Freedom Riders. “I heard them crying for water. And water is a basic need — I mean you don’t have to be political to give someone water who needs it.” —JFM

Humans are mundane, his knew first and we've all come to that realization. I love your writing style my friend. I'm mostly captivated by the slight additiona of historical sentences. It's awesome, the work here. And I love it