The flight attendant always demonstrates that oxygen mask thing, but I never thought I’d need it. “In the event that our cabin experiences pressure loss, air masks will be deployed. Secure the mask over your face like this and tighten the straps. The bag may not inflate . . .”

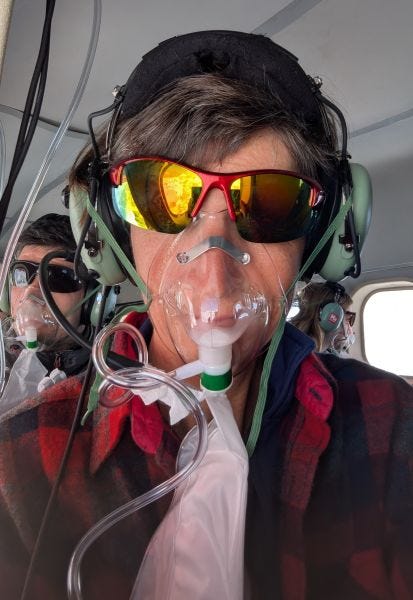

Before we boarded the aircraft, a single engine, high-wing propellor plane called a de Havilland Otter, our young solo pilot laughed that he was also the tour guide and the lone flight attendant. He apologized there would be no beverage and snack service or onboard restroom, and suggested we’d better pay attention to the safety demonstration, since he wouldn’t really be able to leave the controls in his pilot seat to help anyone. Before he let us climb up into the airplane, he showed us how to buckle our seatbelts, how to operate our oxygen masks, how to open the exit doors, and where the first aid kit was located. In contrast to a commercial passenger jet flight, no one was scrolling on their phone during this safety demonstration. All eight of us passengers paid close attention.

The plane was older than any of us on board. Only 466 of these Otters were ever made, between the years of 1951 and 1967, and they have been such consistently reliable workhorses ever since that most of them are still in use regularly. Our flight would take place in a red 1955 model, built the same year:

Rosa Parks sparked the Montgomery bus boycott

the polio vaccine was approved

Bill Hailey and His Comets topped the Billboard charts with their hit, “Rock Around the Clock”

Dwight D. Eisenhower became the first U.S. President to appear on color television and raised the federal minimum wage by 33%—from seventy-five cents to a dollar an hour

Surely, that little red plane has some stories to tell.

I will admit, though, I was fighting disappointment. We had hoped for a sunny day. The weather forecast had promised a sunny day. We wouldn’t have spent that much money had we not expected an amazing view set against a brilliant blue sky—a rare treat for southcentral Alaska.

And even though our local Alaskan friends had emphasized that weather forecasts here are unreliable, that Alaska’s weather patterns are not exactly pattern-based—less science and more interpretive dance—this time it looked like we would strike gold. This time, even our Alaskan friends encouraged us to book the flight immediately, before the high-pressure system collapsed. It was a record-setting weekend across much of the state. Fairbanks, which sits at a higher latitude than Reykjavik, Iceland, registered 85F degrees.

So we did it. We changed our plans and booked a flight, then packed up Walter, our big yellow adventure truck, and drove to the little airport in Talkeetna for a flightseeing tour of the tallest mountain on the North American continent. But the sky—and increasingly, my mood—was heavy with clouds the whole way there. By the time we entered the lobby where we were to check in, the room was abuzz with crackling radios and conversations about whether or not the upcoming flights would be cancelled.

But a little bit of blue started to poke through. They didn’t cancel.

We boarded, zoomed down the short runway, and lifted off, watching the little airport below turn into a Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood set of miniatures. Within less than a minute, our earth-bound perspective had changed dramatically. I gazed out my little window and saw no trace of humanity, only wilderness—boggy peat moss terrain known locally as muskeg, stunted and shrubby boreal forests, meandering streams; and in the distance, inky indigo mountains with their tops chopped off by the heavy layer of gray.

At eleven o’clock in the morning, under a cloudy sky, the light was flat. No sun means no shadows. And it’s the shadows that provide visual stimulation to our brains—there is data to interpret when shadows are cast, and our brains love a challenge, however small. Shadows are dramatic. After years as a photographer, I understand this. Even in the sunshine, photos of beautiful scenes can come off as boring if there are no shadows.1

But we had splurged on this flight, and getting up in a small plane is always a good thing. Forcing myself into positivity, I decided to enjoy whatever visibility we got. I hoped conditions might improve as we climbed higher and the midday sun warmed the air, but just getting a fresh perspective on the wild land would be a win.

We ascended into the cloud layer, gauzy at first, then thick and stifling. At 7,000 feet, we broke the surface like a diver coming up for air. I looked around, hoping for glorious blue sky. Hmmm . . . I lifted my borrowed sunglasses, which blocked the glare with an industrial-strength passion, but no, it wasn’t the dark lenses. It was the sky, cloudless, but tinted a designer shade of taupe, or perhaps mushroom.

The pilot’s voice crackled into our headsets. “Well, folks, it looks like this morning’s easterly breeze brought us the smoke from Canada’s wildfires.”

I stared out at the mountains—beautiful mountains, streaked with snow, glaciers by the dozen as far as the eye could see. But hanging over everything, like a thick layer of dust on an otherwise elegant grand piano, was a filmy cloak of gray-brown smoke. Pull it together, Sherry, I chastised myself. Our Canadian friends are suffering through damaging fires and terrible air quality and disruptive evacuations and frustrating road closures, and all you can think about is how the smoke tints your scenic view? I felt disappointed at myself for feeling disappointed.

“There’s our first peek at Denali. You can see it poking through off to the left there in the distance.”

I craned my body into the narrow aisle toward my husband and tried to look out his window. The angle was wrong. I couldn’t see the peak. I looked forward through the pilot’s windshield view, but the nose was already pointed up.

“We’ll climb a little higher as we head over there.”

My ears popped several more times as we gained altitude.

Perspective is such a simple concept, right? Technically speaking, it’s the view one has based on their location relative to other objects and their distance from the horizon.

From on the ground, for instance, I could see the delicate wildflowers along the edge of the tarmac, but I couldn’t see anything beyond the line of trees in front of me and the clouds overhead.

As we rose above the earth, I could see where the clumps of shrubbery gathered along the water’s edge, then gave way to the spongy, mustard-colored muskeg. I could discern where the rolling hills had been scrubbed smooth by deep glaciers but left sharp and craggy where they’d been tall enough to rise above the ice. I could follow where the rivulets joined to form streams, the streams converged into rivers, and the rivers diverged into branches.

Then, from above the cloud layer, I could see the endless mountain peaks that show so clearly why only 20% of Alaska is accessible by road. But from 7,000 feet, I could also see the brown layer of smoke I hadn’t been aware of before. Every time our altitude changed, my attitude was impacted. I gained a broader perspective.

Even through the smoke, though, it was quite a view. We continued to climb, steadily gaining altitude. Having long since passed the last of the vegetation, the peaks beneath us grew gradually whiter. Now we were seeing less exposed granite and quartz, and more snow and ice. The biggest peaks seemed to rapidly grow in size as we approached. I scanned the tops, comparing the sizes. I assumed one of them had to be Denali.

Since the small plane’s cabin was unpressurized, we knew we’d need to begin donning our oxygen masks2 once we’d climbed to 12,000 feet. When the pilot gave the instruction to do just that, we were ready. I wrestled with my mask, my child sized face not long enough to make my mask fit well. Finally, I thought to lift my sunglasses up and tuck the top of the mask under them, then clamp the nose piece tighter to jam it into place. It was not completely comfortable, but it worked just fine. The cool oxygen streamed into my nostrils—a most pleasant sensation.

When I looked up again, the scene had changed dramatically—this time for the better. Wow. We had risen above the layer of smoke and the air was suddenly crystal clear. Wow. Wow. Wow. It might have, at least proverbially, taken my breath away, but no—I was equipped with supplemental oxygen, and I was not afraid to use it. Bring on the wow.

We were right on top of the mountains now. A red airplane wing, above the white peaks surrounded by a brilliant blue sky. It was downright patriotic. I scanned the peaks out my window on the right side of the plane. Which one was Denali?

The pilot’s voice came through the headset. “There it is, folks, in all its glory, on your left. I swear, I have the greatest job in the world—coming up here to show you this. And what a beautiful day it turned out to be! Do you realize how lucky you are?”

I craned my neck again, but the angles were just too difficult. I could tell Andy was transfixed, but I couldn’t see it for myself.

The pilot spoke again. “Hang on—those of you on the right side—I’ll swing us around so you can see, too.” He turned the plane 180 degrees in a steeply banked arc.

Oh.

Oh, my.

My gaze had been too low.

Denali isn’t just one of the tall summits in a line-up of likely suspects. No. It rises alone with regal authority, three to six thousand feet above all the other nearby peaks. In the Lower 48, three to six thousand feet represents respectable mid-sized mountains. Mount Mitchell, in the Appalachian Range, is the highest North American peak east of the Mississippi—and it rises only 6,000 feet above the horizon. The Bitterroot Mountains we loved so much in Montana top out around 10,000 feet, but that is from a 3,400-foot-high head start on the high valley floor, so visually, they are only 6,000 feet, as well.

Denali jutted up in front of me at a staggering 20,310 feet.

The mountain’s historic name comes from an ancient word that means the tall one or the great one in the Koyukon language. For thousands of years of human existence in these lands, it has been recognized as the peak of peaks, the summit among summits3. Even the first white men to climb it the early 1900s called it by its traditional name, Denali, out of sheer respect, long before its name became a political football4 for rivals to fight over. I sucked in the cool oxygen flowing from my mask and admired the view.

The pilot found a buttery smooth pocket of air at about 19,000 feet, a mile or two from the summit, and slowly trolled back and forth, allowing us to fill our camera rolls and cement the images in our minds. We watched the human climbers, like ants, leaving their various camps, and making their ascents up the steep ridgelines. Karen Carpenter’s smooth voice echoed in my head. Truly, we were on the top of the world, looking down on creation.

Perspective

We were on land, and I couldn’t see anything encouraging. We lifted into the air and all I noted was the flat and dull light. We climbed above the clouds, and I was disappointed to find brown smoke. But then we climbed above the smoke and the sky suddenly turned blue and I thought it was the most amazing sight I’ll ever see. I thought the 14,000 to 17,000 footers were incredible. I’d seen a couple of 14ers in the distance in Colorado, but never up close, and never from the air. I assumed one of the 17ers in my view must be Denali, and I had seen enough to be more than satisfied, even before I ascertained which one it was. They were all incredible, wilder than anything I’d ever known, and to see them from the air, contrasted against that deep blue sky, would clearly be one of the greatest highlights of my life.

But then the plane circled around so I could see the main attraction. Wow. Denali stood head and shoulders above the others. Magnificent. Majestic. Awesome. Like Nat King Cole crooned in 1946, it was just too marvelous, too marvelous for words. It was more than I could have ever thought to ask—or even think.

Only 30% of people who visit Denali National Park actually get to see the peak of The Great One. It’s usually shrouded in clouds—even on clear days—creating its own weather system at such lofty heights. Viewing it at all—even just a peek of the peak, puts a person in the unofficial Thirty Percent Club. Having now seen the summit at its finest, Andy and I are exclusive members.

But as great as the sight itself, at least for me, is the lesson learned. From majestic Denali, I was reminded: we can’t see what we can’t see. We can’t imagine what it will be like. We won’t know until we are there. Why worry? Who, by worrying, can add anything positive to their lives?

And there’s no guarantee, but things might just turn out better than we could have ever imagined.

Until next week,

Sherry

The best time to shoot scenic photos is at Golden Hour—the hour just after sunrise or just before sunset—when the shadows are long and the light, filtered horizontally through the atmospheric layers, is warm. Flat light is favorable when shooting portraits, however, as harsh shadows can interfere with facial features and skin tones.

Sure enough, when donning an aircraft’s oxygen mask, some of the bags don’t inflate. Andy’s did; mine did not. But the air flowed to both of us just the same. It’s one of life’s great mysteries.

To be fair, Mt. Denali is not that tall, compared to the rest of the world’s tall mountains. There are eight entire ranges of peaks larger than this one in Asia, and Mt. Everest tops out at over 29K feet, compared to Denali’s 20K. BUT, these other tall peaks emerge from high plateaus. Denali does not. That means, measured against sea level, Everest et al. are much taller, but measured visually, from base to peak, Denali is the tallest. Perspective.

In my opinion, the name Denali assigns the mountain the dignity it deserves—much better than a politically-driven endorsement of a then-candidate for president who never ended up visiting Alaska or making any policies impacting it.

Hello! Having spent 3, yes 3 summer seasons in Denali National Park, I have had the privilege of seeing ’her’ many times. Fabulous place on the ground and in the air! Say hello to Anchorage for me.🥰

Jealous! Our flight-seeing was canceled due to weather. But I’m glad you got to see Denali especially because you described it so beautifully.

Also, perhaps the oxygen mask doesn’t fit because like nearly everything, they are designed to fit men. I’d wager other women have the same issue. (Read the book Invisible Women if you don’t have enough righteous indignation in your life.)