CANADA Part 4: Small-town stories with strangers

Returning to the Yukon after four decades away

The drone buzzed around my head in a slow circle like a giant cyborg mosquito, but I was not intimidated. Looking straight up into its prying eye, I called out with authority the words I’d been waiting four decades to say.

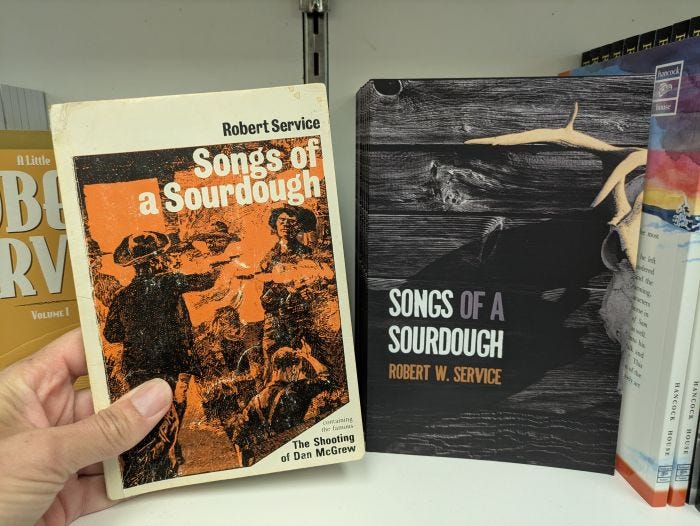

I suppose the other visitors to Lake LaBerge and Miles Canyon thought I was a little crazy, but I had returned, triumphant, and this was my moment. I had my original 1980s paperback book of Robert W. Service’s poetry, and I was not afraid to use it.

Because I’ve already written previously about my history with Service’s long narrative poem, The Cremation of Sam McGee, I won’t go into all the details here. But for forty years, I have wanted to recite this particular ballad into the wild open spaces of the Yukon Territory. If you are curious about why—and who wouldn’t be, haha—you can read what I wrote last year about my Robert Service fixation by clicking the link here:

Six weeks after I wrote that post, last year, I had the opportunity to recite the ballad at the Northwest Nomads gathering near Bend, Oregon. It was well-received there, which only encouraged my mad obsession. If my fellow-nomads, snuggled up in flannels and blankets under a starry sky, appreciated my poetry recital, then certainly the Yukon’s rocks and trees, lakes and rivers would prove to be a receptive audience.

This past week, with two days to get reacquainted with the Whitehorse area, I was finally reunited with the shore of Lake LaBerge (referred to as “the marge of Lake LaBarge” in the poem), as well as the winding turquoise river of Miles Canyon—where the sternwheelers of the gold rush era squeezed through the narrow, steep walls amidst dangerous currents.

Andy, my cinematography-minded husband, offered to film me reciting the poem and make a YouTube video of it for our channel, taking my forty-year dream up a notch. I looked around at the beauty of the natural environment all around me. Then here, said I, with a sudden cry, is my wild podium.1

Filming my recitation was fun but a little challenging. Others in my family are theatre people—but not me. Although I am comfortable on a stage as myself, an educator and public speaker, I have never been an actor. This little project pushed me beyond my comfort zone, but I claim to be comfortable being uncomfortable.

So, I pushed beyond what I thought I could do, and—lo and behold—I did it. You can watch the finished result of my efforts, magically transformed into a full-scale production by Andy’s video skills, at the end of this post.

Once the filming was finished, I still had some time to explore the small city of Whitehorse which, at a bustling 37,000 people, contains nearly 80% of the Yukon’s entire population. While Andy worked on his video projects, I walked the town—top to bottom, front to back, inside and out. A few landmarks look the same as I remember them, like these:

But much of the town would be completely unrecognizable to those who remember it from long ago. Some of it is just basic growth. Having more than doubled in population from when I visited in the mid-1980s to today, there are understandably many new and refurbished buildings around town. But what struck me the most was the variety of people. Whitehorse used to be a fairly dichromatic mix of Caucasians, who settled there during and after the 1898 gold rush era; and the longstanding indigenous people who had lived off the land there for thousands of years. In 2025, it is the full box of Crayola’s Colors of the World—their skin tone mix—all of them bundled up against the cold and living the Yukon life side-by-side.

From a couple of isolated comments I overheard, I am guessing the new multiculturalism in Whitehorse has led to at least a little bit of tension in the city. There may be some resentment among those of limited melanin who tend to believe—whether consciously or subconsciously— that they are more important than those with more melanin. Perhaps because their ancestors immigrated earlier than these relative newcomers, some may feel deep-down that they are more worthy of belonging in the Great White North than those whose skin is at the darker end of that Crayola mix and immigrated from non-European nations. But for lovers of all things cross-cultural like myself, the new diversity was refreshingly beautiful. (And, I might add, the “international” section of the grocery store was enormous and a.ma.zing for such a small city.)

I wanted to know why, though. Why would so many people from places with much warmer winters relocate to the Yukon? I walked down to the farmer’s market2 at the park, hoping to talk to find some answers.

The farmer’s market was a much bigger deal than I’d expected—especially for this early in the season when there’s no produce available to sell. A circle of white tented booths ringed a gorgeous new playground in the middle of the park—filled with parents and children, strollers and puppies, and playground equipment so creative and fun I wanted to try it myself. I made two slow laps around the booths, admiring jewelry and textiles, paintings and finely crafted leatherwork, vegetable starts and dog treats. I sampled several varieties of the locally made Cold Snap potato chips, as well as a family-run booth offering homemade granola bars—all were delicious. I politely declined the samples from a local coffee roaster, but it smelled heavenly. The food truck end of the park circled an open grassy area nearly the size of a ball field and, judging from the enthusiasm of the crowds gathered around each of the dozens of trucks, the food was delicious. I texted Andy to stop working and walk down to the park to join me for dinner.

With half an hour to wait before he could arrive, though, I needed something to do. Browsing slowly—after walking briskly all afternoon—was not enough to keep me warm in the North of 603 chill. I was not sufficiently acclimated or dressed for it, as the temperature had begun to drop and the breeze had become quite brisk. Looking around, I noticed a modern building close to the playground. Hardier folk than me crowded around picnic tables outside the building, engaged in conversation as they enjoyed their food truck purchases. Behind them, other people walked freely in and out of the doors on either side of the building. Perhaps it was a community center of some sort. I went to investigate.

Standing outside, in the shadow of the building, effectively blocked the wind, but I was still chilled. I opened the heavy glass door and stepped inside, a little chagrined at my own lack of preparation for the cold, but grateful for a warm location in which to wait.

As my eyes adjusted to the dimly lit room, I looked around at my options. Half a dozen round tables hosted assorted small groups of diners. I knew this would be a great place to strike up a conversation with a stranger, but suddenly, I felt shy. When Andy is with me, it’s easier. Meeting strangers, after all, is his superpower. But these people were already in groups, oohing and aahing over each other’s food and shooting the breeze about local daily life—school and work and such. I was alone, with no food or common experiences to discuss. Sitting down at the one empty table in the room, I felt as awkward as Walter, our big yellow adventure truck, must have felt the night before when we accidentally interrupted a German sportscar club’s photoshoot.

Moments later, two women about my age walked in with their food truck dinners. They scanned the room—including my wide-open table—then walked to another table that was already half full and asked if they could sit there. Of course, the answer was yes. My answer would have been yes, too, had they only asked.

Hmmm . . .

The next people to enter the building appeared to be an extended family group or friends, two men and three women in perhaps their thirties. All of them were carrying food, and one of the women also carried an infant in one arm. They looked past my table at the rest of the room. A group of that size wouldn’t fit easily at any other table.

“You can sit here,” I blurted out, perhaps a little too eagerly.

They thanked me and filled most of the seats, then began to talk amongst themselves. I noted they all had chosen Indian food, which matched my first impression of their ethnicities. They passed their foil packets around among themselves, each one reaching into the others’ bags with their fingers, then commenting on the flavors as they popped apparently tasty morsels into their mouths. The mama broke small bits off some of the items, mashed them between her fingers, and placed them into her hungry babe’s mouth.

I had to break into the conversation. This was my chance.

“I was thinking about which food truck I should try,” I interjected. “It looks like you found a good one.” My tone came out as a question, rather than a statement—an invitation to conversation.

“Oh, yes!” one man replied. “This is very good.”

The others quickly jumped in, supporting his assessment.

“Do you like Indian food?”

“I do. Absolutely.”

“Would you like to try it?” One person held out their foil packet toward me.

“Oh, no, that’s ok,” I tried to refuse, but I was immediately overruled by the entire group, talking at once.

“No, really, you must try it. It’s delicious—very authentic.”

“Here, please try this one, too!”

This was more than I’d bargained for, especially as I realized they were all eating with their hands, culturally appropriate for Indian cuisine. I hesitated. Five friendly but insistent faces and several packets of food—which smelled incredible, I might add—were being held out to me, arms reaching toward the center of the round table like spokes on a wagon wheel.

I showed my empty hand, demonstrating that I had no fork with which to dip, and started to protest.

“No, no, it’s fine!” they insisted. “We all share food like this.”

Delicately, I reached my fingers into one bag after another, popping a sample of each into my mouth. Their faces lit with joy as I outwardly expressed my tastebuds’ inner delight.

“You like it?”

Mouth full, I nodded vigorously and gave a closed-lips smile.

“Ah, I knew you would! The woman at that booth over there is very talented.”

Sampling their food, fingers and all, broke the ice and allowed conversation to flow freely—like the spring break-up on a frozen river.

We all had questions about each other. Though I forgot to ask if they were family or friends—or a combination of each—I did learn they are all from the same region of southern India, having moved to Canada for work in the medical and educational fields. Some arrived five years ago or more, first working in Ontario before moving to the Yukon. Others arrived just over a year ago, coming straight to Whitehorse.

“But why Whitehorse?” I asked, genuinely baffled.

They explained that Whitehorse pays top wages in these professional fields. The population is small, and so many of the local young people are anxious to move to the bigger cities with better climates, more social opportunities, and generally a more modern lifestyle with more things to do. That leaves the local hospital and university woefully understaffed, willing to offer top wages and excellent benefits to qualified applicants.

Though they all admitted adjusting to the cold had proved difficult at first, having come from one of the consistently hottest places on earth, now they don’t mind it so much. In fact, now they have trouble when they go back to India to visit their families. They find the heat there absolutely unbearable. At least with the cold, one can keep layering on more clothes.

But do they actually like living here?

The consensus was yes. Whitehorse is a supportive community, and enough Indians have moved to town that good Indian food is readily available. The pace of life is slower in this small town than in the chaotic big cities they left behind, and everything is close by, so there’s no need for a long commute in the smog. Recreational opportunities abound, and getting out in the beauty of nature is hard to beat. They are truly happy, living in the Yukon.

Finished with their meal, they were ready to move on. Our farewell was full of warm smiles and handshakes, with no trace of so recently being total strangers to each other.

I was considering going back outside myself when another couple came in the room and asked if they could sit at my table to eat. I motioned my consent and smiled. They, too, had skin a few shades darker than mine. I didn’t immediately recognize their heavily accented English. Emboldened by my previous encounter, I opened a conversation right away.

They were from Quito, Ecuador, likewise recent arrivals here on a three-year work visa. She had arrived several months ago. He had joined her only two weeks ago. Both were bundled up far beyond my own t-shirt, flannel, and hoodie.

Their English was quite good—better than my Spanish—but it was obviously still work for them to function in a second language. When they slipped into Spanish momentarily to clarify something with each other, I showed my understanding and chimed in. Ah, they were relieved that I spoke some Spanish—even if it was a little rusty, having left Mexico behind back in March. We switched back and forth between the languages when one of us got stuck.

Their story, though their arrival was more recent, was much the same as the Indian immigrants I’d just met. The wages were hard to beat and the lifestyle, in the midst of beautiful scenery, was agreeable. The cold would require some time to adjust, but they would stick it out for the extent of their visas to see if they wanted to renew or return to Ecuador.

After this initial exchange of who we are and what we were doing in this remote region of the Far North, our conversation shifted to where Andy and I should go when we make it to Ecuador, their home country. I took copious notes as they told me about places I must see, as well as a few places we should probably avoid. By the time Andy himself joined us at the table, we were quickly becoming friends, exchanging contact info and cheering for each other’s epic adventures.

Promising to stay in touch via WhatsApp, we agreed that they should always address us in English, as they need the practice, and we should address them in Spanish for the same reason. More smiles and handshakes. More genuine best wishes all around.

Truly, I love multicultural settings. I hadn’t expected to encounter such cultural diversity in Canada’s rugged Yukon Territory, but I’m so glad I did.

But wait! My paperback of Robert W. Service’s poems! I’d left it on the “marge of Lake LaBarge” when we were filming my recitation video!

Too bad. Although I hated the thought of littering like that, my newly found minimalism was willing to let it go. How absolutely poetic that the little paperback of poems I’d treasured for all those years had come back full circle and would meet its end on the “marge of Lake LaBarge,” washed away as the impending snowmelt filled the lakebed. A forty-five-minute drive, each way, was definitely too far to go back and retrieve it.

But Andy insisted. It was well after 11 PM when we reached the shore of Lake LaBerge again, but, in the fading light of the Midnight Sun, I found it—tucked under a rock, right where I’d left it.

I suppose it was indifferent, technically speaking, but I’d prefer to believe that, like the land itself, it was patiently waiting for my return.

Until next week,

Sherry

P.S. Here’s that video I promised, thanks to my hardworking husband who put this together in only a few days so I could share it with you, dear reader:

(I’d love to know what you think. Leave a comment and/or share it with a friend who might enjoy it.)

Wild podium sort of rhymes with crematorium, right? I admit, it was a cheap rip-off of one of the more dramatic moments in the actual poem, but I couldn’t resist. If you aren’t familiar with Service’s most famous poem, you can read it in its entirety here.

Whitehorse’s Fireweed Community Market can be found at Shipyard Park on Thursdays, 3-7 PM, May-September. Even though May is too early for produce, the arts and crafts, baked goods and canned goods, beauty products and beverages are abundant—and the food truck scene, showcasing truly authentic flavors of the world, is STRONG. Try the Indian food booth way over by the community center. Wowza.

‘North of 60’ refers to land above the 60th parallel of latitude, a significant line of demarcation, as it delineates the southern provinces from the three northern territories in western Canada.

I enjoyed hearing your rendition of Sam McGee. I remember Biff Copeland used to recite that poem around the campfire at YMCA Family camp every summer at Lake Sequoia. Great poem. Well presented!

Love the video and the story telling! Great job for both of you. I am really enjoying your travel posts. What a life! Much envy from me!! May God bless you and keep you safe! Helen